Christmas and meaning

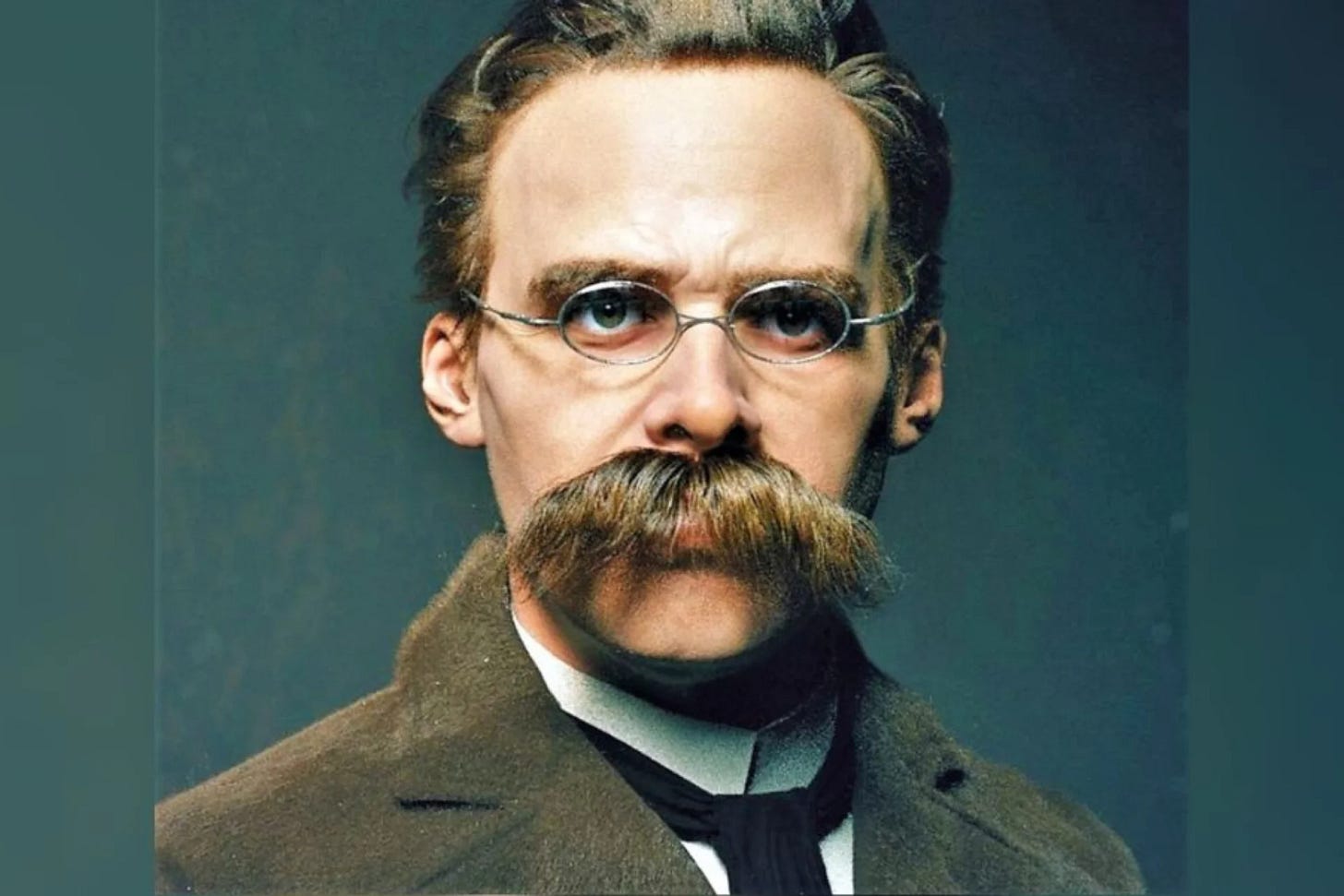

We invited the Reverend Ross Hathway to post a Christmas message. He considers the challenges to Christian belief posed by the German philosophers Friedrich Nietzsche and Martin Heidegger

In the late 19th century, the German philosopher Nietzsche (who was so influential but misunderstood in the thinking of the Nazis) foresaw the rolling back of the ‘sacred canopy’ of Christianity and the exposure of the empty heavens.

A moment of potentially shattering crisis had arrived1; and it was not obvious to him that post-Christian humanity had the energy to respond to it with anything more than an ever-deeper descent into triviality and narcissism - the belief that life is meaningless - nihilism.

The "death of God" had certainly come, he believed - which is to say that belief in anything transcendent, beyond ourselves has ceased to be even a possibility, except for delusional people. What then will "godless humanity," become? It may well be that, when Christianity passes away from a culture, nihilism is the inevitable consequence, precisely because of what Christianity itself is.

Nietzsche’s view was this: Once, ages ago, the revolution that the coming of Jesus Christ (the ‘Gospel’) brought into the ancient world discredited the entire sacred order of the old pagan religions of antiquity. Christianity took the gods away, subdued them so utterly that, try though we might, we can never really believe in them again. So powerful was the new religion's embrace of reality, and so comprehensive its effects, that even the highest achievements of antique pagan wisdom were easily assumed into its own new intellectual, aesthetic, and ethical synthesis.

When, therefore, Christianity departs, what is left behind? It may be that Christianity is the midwife of nihilism precisely because, in rejecting it, a people then necessarily reject everything except the bare horizon of the undetermined human will. No other god can now be found.

The story of the baby Jesus who grew to be the crucified God took everything to itself, and so - in departing - took everything with it: habits of reverence and restraint, awe, the command of that which is Good within us.

Now there is only the power of our own wills, set before the abyss of limitless possibility, seeking its way - or forging its way - in the dark. What, though, arises from such a condition? The horrors of twentieth Century Nazism and Communism now discredited? Yes! But another answer is what has now arisen in the West: mere boredom and banality. And surprise, surprise without a compass, demagoguery.

Nietzsche's himself feared the loss of any transcendent aspiration i.e. something beyond ourselves.

As I look at our culture today there for all to see is our culture's devotion to acquisition, celebrity status, distraction, and therapy. It’s hard not to think that perhaps our vision as a people has narrowed to the smaller preoccupations and desires of individual selves, and that our whole political, social, and economic existence is oriented toward that reality.

On the other hand, perhaps that is simply what happens when human beings are liberated from want and worry, and we should therefore gratefully embrace the triviality of a world that revolves around television, shopping, and the Internet as a kind of blessedness that our ancestors, oppressed by miseries we can scarcely now imagine, never even hoped to enjoy in this world.

Nietzsche's himself feared the loss of any transcendent aspiration i.e. something beyond ourselves. He realized we should never cease to be somewhat apprehensive regarding our own capacity to destroy or corrupt things that, as individuals, we might be disposed to treat with reverence or respect.

Martin Heidegger2 was a twentieth-century philosopher who pondered the origins and nature of nihilism. For him the essential impulse of nihilism arises first from a long history of human forgetfulness of and indifference toward the ‘mystery of being’.

This is aided and abetted by the desire to master reality by the exercise of human power. Over many cultural and philosophical epochs, he believed, this drive to reduce the mystery of our being to a passive object of the intellect and will has brought us at last to the "age of technology," in which we have come to view all of reality and the world about us as nothing more than a neutral reserve of material resources waiting to be exploited by us. Technological mastery, he believed, has become for us not merely our guiding ideal but our only convincing model of truth, one that has already shaped our whole understanding of nature, society, and the human being.

In the end what we have is mediocrity, even apathy. This was Nietzsche's greatest fear: the loss of any transcendent aspiration that could coax mighty works of cultural imagination out of a people. When the aspiring ape ceases to think himself a fallen angel, perhaps he will inevitably resign himself to being an ape, and then become contented with his lot, and ultimately even rejoice that the universe demands little more from him than an ape's contentment.

If nothing else, it seems certain that post-Christian civilization will always lack the spiritual resources, or the organizing myth, necessary to produce anything like the cultural wonders that sprang up under the sheltering canopy of the religion of the God-man who we scarcely remember at Christmas time and yet as a people made us great.

Much of the material for this article is indebted to Atheist Delusions by David Bentley Hart, Sheridan Books 2009.

YouTube has an entertaining introduction to Martin Heidegger: https://images.app.goo.gl/rBuC8f8YuLVbEGey7